John O'Donnell Stadium in the Quad Cities was flooded in 1993.

John O'Donnell Stadium in the Quad Cities was flooded in 1993.These people are angels of mercy. I know this from having spent some time with them in 1993, when floods devastated big chunks of Missouri, Iowa and Illinois.

I was finishing a travel story in St. Louis when I got a call from the editors to send my wife home, rent a car and catch up with a team of Red Cross volunteers from Flint who were headed to Iowa.

The flooding was national news, and there was plenty of evidence in St. Louis, where the Mississippi was climbing the steps to the Arch.

Julie, a Mizzou friend and Tony on the steps to the Arch. Look at the flagpoles to see how high the water was in St. Louis.

Julie, a Mizzou friend and Tony on the steps to the Arch. Look at the flagpoles to see how high the water was in St. Louis.But I was amazed by the size of the devastation on the outlying farmlands I saw while driving north on U.S. 61 through Quincy and Alton and Keokuk. Take away an occasional tree top, power line or silo, and I would have thought I was passing Lake Michigan instead of miles of crops.

The water level had already started to slip back by the time I reached southeastern Iowa. I’ll never forget the stench of the water, which smelled like rotting garbage. And there were flies everywhere.

Just touching the water was considered dangerous, and tetanus shots were dispensed like breakfast.

It was in this kind of environment that I caught up with the volunteers from the Flint area. Some were based in high schools, helping people get their lives back in order and providing a shoulder to cry on.

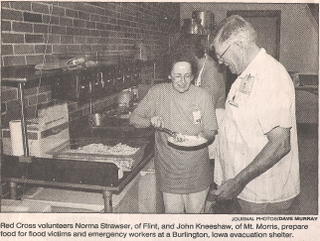

I was amazed at how much the Red Cross provided — clothes, food, cleaning supplies, mattresses and hotel space until homes were livable again. All of which is provided through donations from folks like you and me.  Two of the Flint volunteers preparing meals.

Two of the Flint volunteers preparing meals.

The goal is to get people out of the shelters as quickly as possible, because there is nothing dignified about sleeping on cots in a high school gym with your possessions stacked around you.

Others volunteers hit the road, bringing meals to National Guard members and ordinary folks stuffing sandbags along the swelling Des Moines and Mississippi rivers.

Two volunteers I helped deliver meals to a fire hall near sand-bagging operations.

Volunteers are asked to stay about three weeks, which is about as long as a person can last before enthusiasm and energy dissolve into depression and exhaustion. And they were largely the kind of people who can take three weeks off from work, a lot of good-hearted retirees, teachers in the summer and people with home businesses.

A helper named Norma was dubbed "The Sandwich Queen" for her ability to quickly turn 80-pound stacks of turkey and seven racks of bread into meals.

Others are kind of colorful. One volunteer from Colorado was teamed with the Flintites, and wanted to talk about writing. He said he made good money writing for a particular kind of magazine — the kind with a lot of pictures and very little writing, if you know what I mean.

The impact on these close-knit small towns is hard to describe. One of them, Wapello, was so small that people not only don’t lock their house, but they leave their keys in their cars. It was so small that my arrival was news, and it was known that I had touched water and not yet had a tetanus shot. A nurse from the local public health department tracked me down and gave me the shot.

Wapello, Iowa. A big chunk of downtown was underwater.

The scariest thing happened when I was driving back to St. Louis, crossing a two-lane metal bridge somewhere near Keokuk. It was one of those bridges with the metal grates for a road, and if your car is stopped you can look straight down into the water.

And I was stopped for a while because a backhoe was stretched over the guard rail to dislodge fallen tree trunks and utility poles that had washed downriver and were stuck against a support pillar.

The was rushing quickly, and was so high that it seemed to be only about five feet under the bridge. And at one point I looked upriver and saw something dark bobbing in the water. As it got closer, I realized it was a tree — not a branch, but a full tree. As it got closer I realized there was nowhere I could go, with traffic stopped in both direction.

It finally struck the bridge with a large KLANG, and it seemed to shake for a second, but that was it, and I could exhale.

Naturally, I attempted to work some baseball into the trip. O’Donnell Stadium in the Quad Cities — not too far north of Wapello — was famously under water.

The home of the Burlington Bees had reopened by the time I was leaving Iowa.

The home of the Burlington Bees had reopened by the time I was leaving Iowa.But the Burlington Bees yard was on high ground and not affected. It was locked up tight on the day I had some time to explore. I already had a cool Bees cap anyway. But as I was headed out of town I saw the stadium lights on, a sign that life for these poor folks was slowly returning to normal. As long as there is baseball, things were looking a little better.

2 comments:

Hmmm. I think I have a photo of that. Let me search and add it.

I remember you saying "Step back, step back," as I was taking the photo...

Post a Comment